Tony Wheeler is a trustee of Global Heritage Fund and co-founder of Lonely Planet. Amid reports the venerable publisher may be up for sale again, he recently looked back at the brand’s 45-year history.

Photos and article by Tony Wheeler. This article appeared in the Financial Times.

In July 1972, my wife Maureen and I jumped in a Mini Traveller and left England heading east. I’d just graduated from London Business School with an MBA, and the plan was we’d travel as far as that £65 car would carry us. Times change; these days MBA graduates emerge with a backpack full of debts and need to start earning fast to pay them off. Our backpacks contained some clothes, but they were mainly stuffed with dreams. That dirt-cheap car carried us all the way to Afghanistan.

Months later we arrived, penniless, in Australia, decided our plan to circle the world in a year and “get travel out of our systems” was doomed, and a few months later created something that would ensure we’d never kick our travel habit: Lonely Planet. We didn’t even have a typewriter when we put together that first guidebook. Maureen would bring hers home from the office each Friday night and we’d spend the weekend hammering out the text on the kitchen table in our basement flat in Sydney. Of course we had no idea what we’d stumbled on, although years later it seemed obvious that this was the perfect moment to launch a travel publishing empire: the baby boomers were coming of age, jumbo jets were taking to the air and the hippie trail and the “Marrakesh Express” were on every young traveller’s mind.

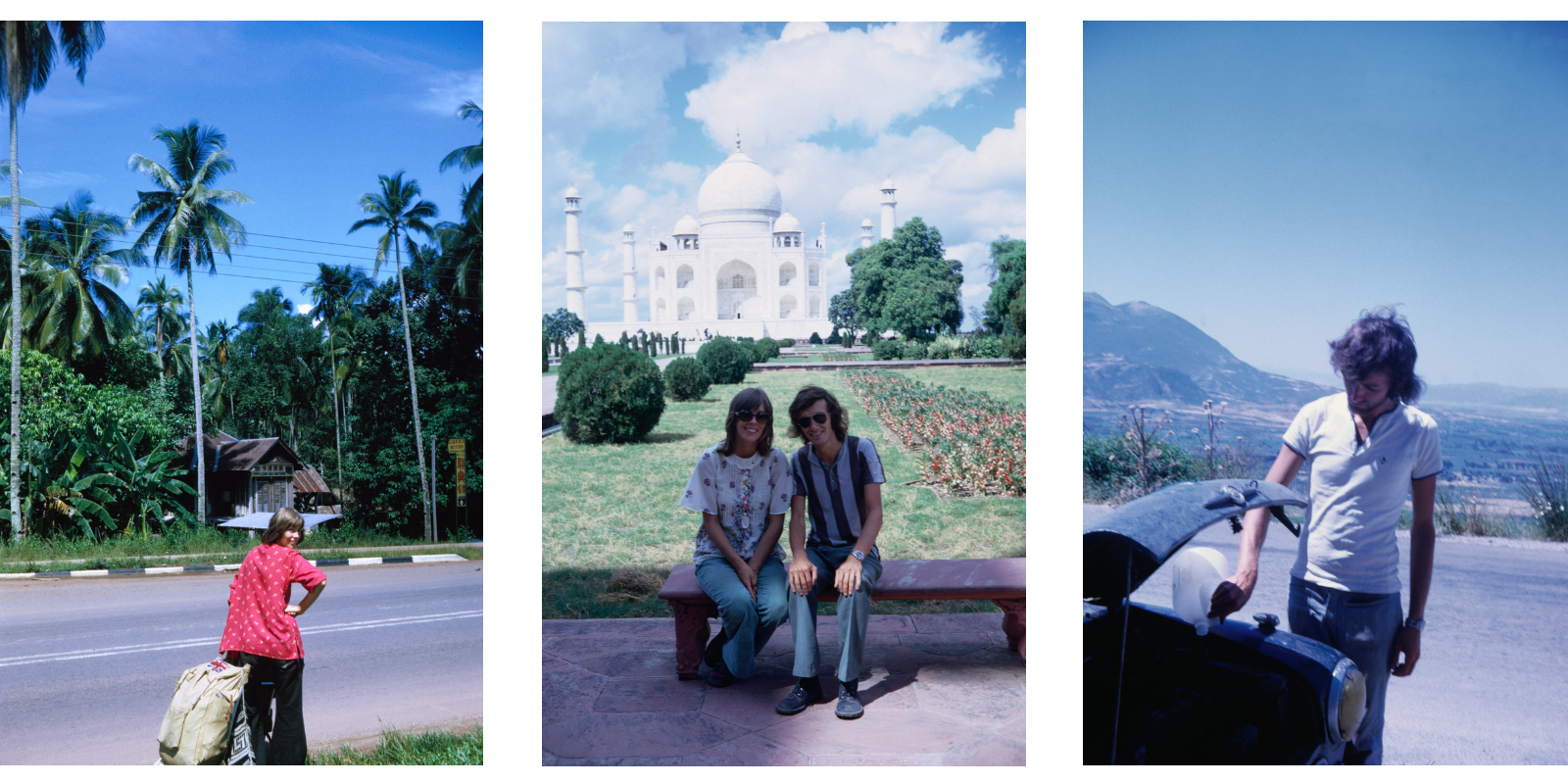

Hitchhiking in southern Thailand; at the Taj Mahal in Agra; in Greece.

A year later we were exploring south-east Asia on a motorcycle, but by this time our travels were completely different. The first trip across Asia had been enormous fun, but the idea that it was the foundation for an international business certainly wasn’t part of the picture. On trip two we could visualise the guide that would follow from the day we rode that motorcycle out of Sydney. In the following years we weren’t surprised when it found its way into so many backpacks. With edition 19 appearing soon, sales of Southeast Asia on a Shoestring are now in the millions.

We were, however, very surprised when that one book was followed by hundreds of others, Lonely Planet offices popped up around the world and each year we unleashed what felt like an army of writers, researchers, photographers and cartographers to explore every country on Earth. Almost from the beginning I was confident that Lonely Planet would “work”, I just had no idea how well it would work and how a “Lonely Planet traveller” would become shorthand for a certain type of wanderer — not always young, but with an approach to travel and its importance to the world that I felt very strongly about.

At the Wagah border, Pakistan to India.

Though people often assume digital media came as an unwelcome challenge to the guidebook publishers, I think we can claim we were digital pioneers. After all, we were writing our books using that fancy new “word processing” in the early 1980s when most publishers, if they had a computer at all, used it only for accounting. As early as 1994 we had a blog (although the word wasn’t invented for another five years) on Tim O’Reilly’s pioneering Global Network Navigator website. We had our own website soon afterwards and in 2000 we launched CitySync guidebooks on PalmPilots, those pre-smartphone mini-tablets. Nevertheless, I confess, all this digital groundbreaking was not my first passion; I still had a love affair with those old-fashioned print guidebooks.

Lonely Planet wasn’t going to be a family dynasty and by 2007 we felt it was time we departed. We weren’t short of suitors, but the BBC seemed the perfect partner, with the digital muscle and expertise we needed. The message was that just as Top Gear was the BBC footprint in the motoring world, so Lonely Planet would have the same position for travel. We had been successfully turning out Lonely Planet TV programmes since 1994; with the BBC behind us that was bound to grow. The guidebooks would continue, our long-mooted magazine would finally launch, the digital side would grow and with the BBC at the controls it was a no-brainer that TV had to expand dramatically. What could possibly go wrong?

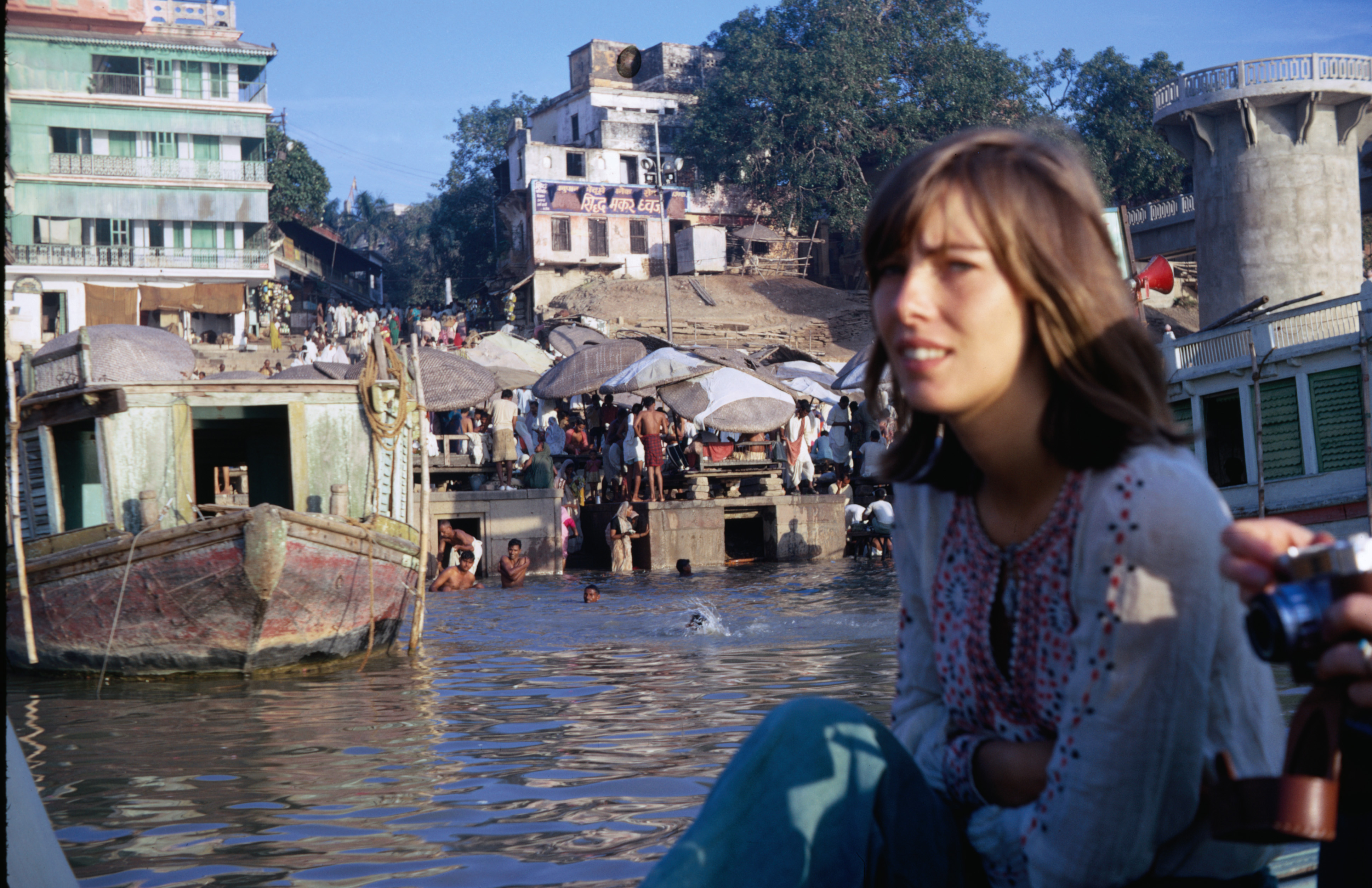

Ganges River, Varanasi.

Plenty, as it turned out. Taking on Lonely Planet would be another step forward for the commercial activities of the BBC’s Worldwide arm, the corporation’s moneymaking side. Unfortunately the BBC periodically seems to go through phases of government concerns about its role and activities and that’s precisely what happened. Suddenly everybody was looking nervously over their shoulders and instead of accelerator to the floor it was a case of slam on the brakes. At Lonely Planet, the books carried on regardless, but all those digital improvements slowed down and, as for TV, well, a couple of years later the whole Lonely Planet TV department got up, walked out and set up shop down the road.

At which point, in 2013, Tennessee-based NC2 Media stepped in and snapped up the company for £51.5m (almost £80m less than the BBC had paid for it). Lonely Planet ownership made another continental leap, Australian to British to American. The new chief executive was 24-year-old Daniel Houghton. Now, five years later, it looks like the ownership could again be in play. This month it emerged that Houghton has departed for Pyxl, a Nashville-based digital marketing agency. Reports by the travel industry news site Skift and The Bookseller suggest that Lonely Planet is pursuing a sale. (A spokesperson told the FT that it is “business as usual” and, while it has been approached by interested parties, no sale is imminent.)

Central Hashish Store, Kathmandu.

Of course, if the price is right, any business is for sale and I have no inside track on what the story is for Lonely Planet (nor any continuing stake in it), but it’s worth noting what did go right during the company’s post-BBC life. Social media and the “wisdom of the masses” may have become the prime source for many people’s travel information needs, but there’s still a huge market for guidebooks and, for the past five years, so I’ve heard, LP sales have continued to grow. Certainly a glance at bookshop shelves almost anywhere (or Amazon stats) will underline that Lonely Planet has taken an increasingly large bite of the whole travel-book field. Lonely Planet is not the only company that has made the pleasant discovery of late that book sales seem to have bottomed out and even rebounded. Plus I’m still a believer in the value of expertly curated information, gathered by a knowledgeable expert, not some random recommendation from the mildly biased brother of the restaurant owner.

Has the golden age of travel faded along with those traditional travel information resources? Not quite — lots of places that once seemed wildly exotic may now seem boringly mundane, but anybody who wants to leave the crowds behind can still do it. I’m routinely amazed how just putting a few more miles between yourself and the nearest airport can make all the difference. Or a few more canals over from St Mark’s Square, if you happen to be in Venice. There are plenty of destinations that, far from being overtouristed, fervently wish they could move out of the undertouristed bracket. Even big destinations such as India and China have amazing locales that still seem to be waiting for their first tourist. Or at least first foreign tourist; these days tourism is definitely not a purely rich-world activity.

Sun Peddler, Benoa Harbour, Bali.

And that may be the clue to where the company’s ownership goes next. Lonely Planet is such a familiar resource in the English language it’s easy to overlook that it’s equally big in a host of other languages. I’m always delighted that Lonely Planet is number one in Italian, but far more important when it comes to business and sales is China, currently going through the same young-adventurous-traveller rocket ride that those audacious western baby boomers took decades ago.

Without guidebook writing as a mission, I still have plenty of reasons to travel, whether it’s for Planet Wheeler, the post-Lonely Planet incarnation of the company’s developing-world education and health foundation, or Global Heritage Fund, the San Francisco-based conservation organisation. Not to mention my own selfish travels, places I go simply because I want to.

Exmouth, Western Australia.

Despite all the changes in our travel world, I’m still delighted to find myself in places that modern mass tourism seems to have bypassed. Two months ago, that meant the futurist-modernist-rationalist (even fascist) architecture of Asmara in Eritrea. Last year I joined a group of MG enthusiasts (I had to buy an old MGB to prove I was worthy) who spent four months driving along the Silk Road all the way from Bangkok, through China, and across most of the ex-Soviet ’Stans en route to London. Or a few years ago I island-hopped through the northern Solomons and landed on a beach on the Papua New Guinea island of Bougainville. This was totally illegal — it’s not an official arrival point into the country — but I’d been told to report to the nearest police station, confess what I’d just done and all would be well. It was. Now isn’t it nice that even in the 21st century we can still find that sort of travel adventure?

Tony Wheeler and Global Heritage Fund CEO Stefaan Poortman featured in a Reddit “Ask Me Anything” session earlier this year. Read about the three historic areas that he thinks are in the greatest danger, how to develop sustainable tourism, and strategies to conserve heritage sites. Oh, and his favorite burger — from a 1970s London spot that “you need a time machine” to visit . Read more…